Here are some things you’re going to need to know in order to do this assignment. If you already know them, great! If not, just keep reading.

- How Notes Work

- How Scales Work

- Melodic Contour

- Disjunct vs. Conjunct Motion

- What is a singable melody?

How Notes Work

You may know that, in “Western” music (which is probably almost all of the music you’ve encountered, unless you’re like a Ravi Shankar super fan), there are 7 notes of the musical alphabet. They are:

A B C D E F G

If you live in a Romance-language speaking place, or Russia, you know these notes as:

La Si Do Re Mi Fa Sol*

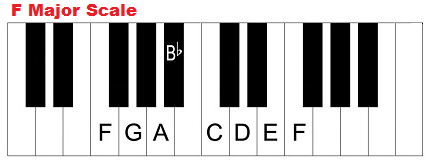

For our purposes, you need to know that each of these notes isn’t the exact same distance apart. A and B, for example, are further apart from one another than are B and C. The reasons for this are complex and have to do with weirdnesses that developed over the course of thousands of years, so please don’t ask why. Just know that B and C are closer to one another than A and B. Maybe looking at this keyboard will help?

Ok, so you can see on the keyboard above that there’s a black key between C and D, another between D and E, none between E and F, then one between each of F and G, G and A, and A and B, before there’s none between B and C. Again, please don’t ask why that is right now. Just memorize that this is the case.

The black keys get called either “flats” or “sharps” depending on whether you think of them as being above a note or below. C#, for example, is the black key above C. Db, on the other hand, is the black key below D. Those both happen to be different names for the exact same note. This is important later.

How Scales Work

To tell the truth, I could do like fifty or sixty whole lessons just about this. This lesson isn’t going to cover how you name a scale, or what kinds of scales there are, or even really how the notes in a scale work. All that stuff is the musical equivalent of learning how to build a shed. Right now, we’re just talking about what bricks are.

OK, so here’s one secret about scales: they pretty much all contain seven or fewer notes. Ta-da!

The general rule is that, in most scales, you only use each member of the musical alphabet one time. To give you a sense of what I mean, let me show you the notes in an F-major scale. They are:

F G A Bb C D E

You may have noticed above that that black key between A and B could be called either A# or Bb–so why do we call that note Bb and not A#? It’s because in this scale, there’s already an A. It would be weird to say a scale contains both an A and an A#.

Well, at the very least it’s not allowed.

So, that’s how scales work at their most basic level. You start with the seven notes, and you can either raise or lower them by making them flat or sharp. Play them in sequence up and down, and you got yourself a scale. That’s all there is to it, really.

Unless you want to start understanding how to name them. That’s like a whole other thing.

Melodic Contour

The term “melodic contour” is just fancy musical jargon for the overall shape of a melody. When a melody moves from one note to the next, it can go either up or down, and it can go up or down a lot or a little. Let’s look at an example.

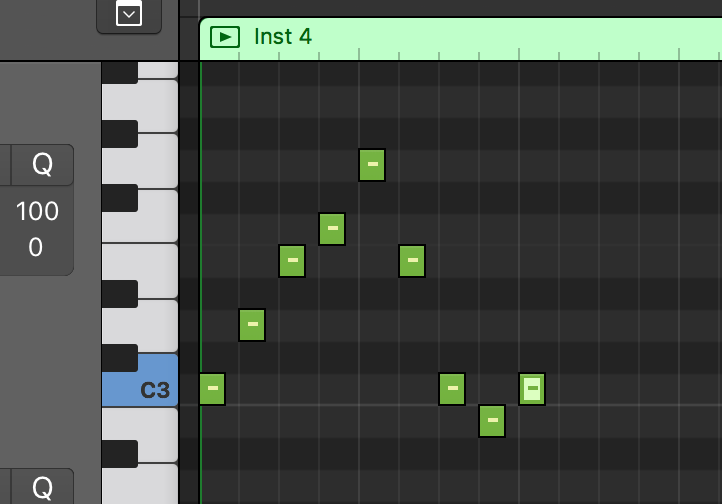

So, you can see here that this melody climbs upward, one note at a time, from the first to the fifth note in the sequence, at which point it falls downward, taking two pretty big leaps followed by one step, then a step back up.

Voila! If you understand this, you more or less get the idea of melodic contour.

Conjunct vs. Disjunct Motion

As I said above, a melody can either move up or down, and it can move either a lot or a little. The jargony terms “conjunct” and “disjunct” are used to describe that last bit: how much a melody moves from one note to the next.

Conjunct motion is motion that only goes from one note in a scale to the next. In the example I gave above, the melody begins with conjunct motion from C up to G, moving one step at a time.

Disjunct motion is motion that skips one or more note in a scale. Some music theory writers like to distinguish between “skips” (in which only one note in a scale is skipped) and “leaps” (in which more than one note is skipped), but not all. After the melody above goes up by step for the first five notes, it skips down for the next two, meaning that that part of the melody uses disjunct motion.

There’s a pretty good YouTube video about this that gives some good examples of these terms at work.

Now, pretty much every melody ever written employs both conjunct and disjunct motion. This is because just one or the other starts to get really boring. That being said, some melodies can be characterized as being more generally conjunct, and some can be characterized as being more generally disjunct. The video linked above gives some good examples of melodies that can be characterized as either, and I’ll include a link to a Spotify playlist I’ve made with tunes that can be characterized as one or the other.

What is a Singable Melody?

Since your assignment this week involves writing a singable melody, I suppose I should define that term. A singable melody is a melody you can sing. If you’ve written a lot of melodies, you probably know that some are better than others–some get stuck in your head really quickly and easily and others don’t. At some future date, I can talk about what makes that happen sometimes and not others. But for now, use your judgment. Your melody is singable if, after you’ve written it, you can walk away from your DAW and still hum the melody to yourself. It’s not if you forget it as soon as you’ve written it down.

Your Homework…

Your “homework” for this lesson is to compose a piece that has a singable melody with a melodic contour that is either:

- LEVEL 1: Characterized primarily by its use of conjunct motion

- LEVEL 2: Characterized primarily by its use of disjunct motion

- LEVEL 3: Characterized primarily by its lack of motion entirely

When you post the link to your piece, please include in your comment the notes you used in your singable melody.

I’ve organized these descriptions the way I have because conjunct melodies are generally easier to sing than disjunct melodies. So you get a level two badge if you can write an easy-to-sing melody that leaps around a lot. Melodies that don’t move at all are really, really hard to make sound interesting. If you can pull that off, you get my unending respect, and a Level 3 badge.

*Yes, Do is not the same note as A. For some reason, English-speaking people started their musical system on the note A (La) while Romance-language speakers start on the note C (Do). I actually don’t know why this is.

5 thoughts on “JBT Music Theory – Assignment #1: Melodic Contour”