I was incredibly, super impressed with all the work everyone submitted. It was really cool to get to hear what people have worked on, and I hope I get to hear even more!

Before you get started on this assignment, you’re going to need to know the following terms:

- Rhythm

- Meter

- Time Signature / Meter Signature

- Compound vs. Simple Meter

- Odd Meter

If you already are familiar with all of the above, that’s great. Just get moving on with the assignment.

Rhythm

If you make music, you’ve definitely heard this term before. Even though we all know what rhythm is, though, defining it in a reasonable way is really difficult, isn’t it? Right now, go ahead and stop reading, and try and write a definition for yourself of what rhythm is.

Ok. You got something? Whatever it is, it’s probably about as good as anything else anyone has come up with. And, to tell the truth, I’d love to hear what you’ve come up with.

The best working definition I can find is here:

Rhythm – The term has more than one meaning. it can mean the basic repetitive pulse of the music, or a pattern that is repeated throughout the music, as in “feel the rhythm”. It can also refer to a pattern in time of a single small group of notes, as in “play this rhythm for me”. (from MusicEZ.com)

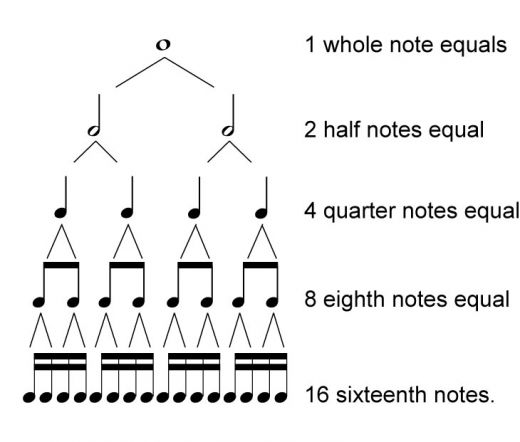

If you’ve taken any music lessons at any point in your life, you know some of the basics of how we write down rhythms. Unless you’re interested in investing some serious time into learning how to sight read—which is a valuable skill, IMHO, but one which takes a lot of time and patience to get even a little bit good at—it’s probably not super important that you learn this by heart right now. But for our purposes, let me include that image that is in every elementary school music teacher’s classroom, everywhere all over the world:

To reiterate, the whole note is 4 beats, the half note is 2, the quarter note is 1, the eighth note is 1/2, etc. Things get a lot more complicated later on.

(By the way, if you’re British, you call those things crotchets, quavers, semiquavers, and so on. It is my honest opinion—and I’m generally open-minded about musical cultures—that that is fucking bullshit).

Meter

If the act of creating rhythm is one of organizing time, the very most basic thing any musical human does is create a regular pulse. A basic, repeating, organized pulse, that occurs at regular, predictable intervals.

The pulse is the most fundamental unit of rhythm, and ultimately it is one thing that unites nearly every type of music that humans create. Though some—well, many—freer form types of music do exist, almost everyone eventually looks for some kind of pulse so that there’s some basic thing to grasp on to.

Once you’ve got your pulse, the next thing to do is to start grouping that pulse into groups.That is probably the simplest way to understand the concept of meter. Meter is just sorting your pulses into groups. It can be groups of 2, 3, 4, 5, 50, whatever.

Now, for those of you who want to get pedantic, I am simplifying this a little bit. In western music, meter refers to beat groupings that have some sort of regular hierarchy, usually with the first beat in the group having the strongest emphasis. In some non-western forms of music (which, as you may remember from post #1, you probably haven’t heard much of), there are beat groupings that are grouped differently. Indian classical music, for example, adds several layers of additional complexity to the grouping of beats, sorting rhythmic structures into complex things called tals that each have specific sorts of emphasis that don’t just occur on the first beat.

Understanding how that works could honestly be a PhD dissertation and then some. So let’s not get too far into that, shall we?

In western music, we call each group of beats a “measure,” and we consistently emphasize the first beat in the measure, which we call the “downbeat” or “the one.”

Time Signature / Meter Signature

Most of my student have some understanding of time signature when they come to me. If you took piano lessons as a kid, you know at least some basic stuff about it. Time signature—which can also be called the meter signature—has got two numbers stacked on top of each other. The top one tells you how many beats are in a measure, the bottom number tells which you note value is “one.”

Over the years, a lot of my students have had a reasonably good understanding of the meaning of the top number. Like, waltzes are in 3 (“1 – 2 – 3, 1 – 2 – 3”), while most rock and hip hop is in four. That’s pretty easy to understand.

The bottom number, though, confuses people a lot. I’ve had many students ask me what 3/2 sounds like, and how it’s different from 3/4. And the true answer is: it’s not really different from 3/4. Or, at least, it doesn’t have to be.

In order to understand that bottom number, you need to know that that image I included above about whole notes, half notes, and so on is a little bit wrong. Maybe even more than a little bit wrong.

So, in a time signature where the bottom number is a four, it is true that a quarter note gets one beat, a half note two, and a whole note four. But if the bottom number is any number but 4—if it is, say, 2—that all goes out the window.

The thing to remember about these note values is that they are proportionate. So a quarter note might sometimes be worth one beat, it might sometimes be worth a half a beat, or worth two beats—but it will always be worth half of whatever a half note is. And a half note will always be half of a whole note.

What the bottom number is telling you is what level of note value is worth one beat. If the bottom number is 4, a quarter note is one beat. If it’s 2, a half note is one beat. If it’s 8, an eighth note is one beat.

This is difficult to understand, because it involves math, and I hope we all can agree that math is annoying and should be avoided if it can be.

If you want a more in-depth explanation of this, ask me about it. For now, just know that the bottom number is usually 4, but can also be any power of 2: 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, and so on. For the most part, the bottom number has basically no effect on how the music sounds beyond a general feeling that certain time signatures imply certain tempos (e.g., 8 on the bottom is usually faster than 4 on the bottom which is usually faster than 2). But if a composer puts 2 on the bottom in their time signature and put instructions to play “very fast,” then that all goes out the window.

If you’re not writing out scores for your music, don’t even bother with any bottom number other than 4.

Compound vs. Simple Meter

Ok, so now that I’ve said all of the above about meter, here’s where we’ll make things even more complicated.

You see, this system of meter signature works really great if you want to divide the beat up into two parts. But, you know, that’s not always what people want to do. Sometimes you want to play a jig, and a jig involves dividing the beat up into three parts. Just listen:

So how do you write out something like that?

In order to capture this, the system that composers eventually landed on was to create a category of meter they called “compound,” which means that it’s dividing the beat by three. You can tell that a meter is compound if the top number in the time signature is divisible by three but isn’t three. So, any meter where the top number is 6, 9, 12, 15… and so on. Those are all compound meters.

If you want to determine how many beats a compound meter has, divide the top number by three. Thus, 6/8 typically has two beats in it, 9/8 has three, 12/8 four, etc. Though most of the time we write compound meters with an 8 as the bottom number, this works with other bottom numbers as well. See here:

If that isn’t complicated enough for you, then there’s how the beat is notated–as you can see above, it’s not necessarily intuitive. At some point in the future I’m going to write a crash course on how to write music in compound meter. But not today.

Compound meters can be super fun, and frequently create a feeling of movement and energy that’s difficult to convey in other meters. Like, if you enjoy a good shuffle? That’s a compound meter beat! How about a lot of African music, or Afro-Caribbean music? Oftentimes, those make use of compound meters.

So, to recap: if a piece of music divides the beat into two (or, by extension, four or eight), then we call it a simple meter. If it divides into three, we call it compound. But, then there’s this other thing.

Odd Meters

If you can’t divide a time signature into 2 or 3, then we call it an odd meter. So, 5, 7, 11, 13, and so on are all odd meter signatures, regardless of the bottom number. There’s a nearly infinite number of ways that odd meters can be put together. I think it’s best we leave this one here.

Your Homework…

This week’s homework has two main parts.

- Find two songs, one in a compound meter and one in a simple meter. Post links to recordings of the songs, along with what you think the time signature likely is for each. For a bonus, include something in an odd meter! That would be fun.

- Pick one of the songs and write an original piece of music in the same time signature as your chosen piece

- This will be due by Friday, May 24th, at Midnight Eastern Standard Time.

When you share your homework on the r/jbtMusicTheory post, include links to your two chosen songs along with the one you’ve recorded in the comments.