In order to complete this week’s assignment, you’ll need to know the following theory concepts:

- What a triad is

- How Triads Work

- How to Name a Triad

- What a chord progression is

- Common chords that aren’t triads

What a triad is

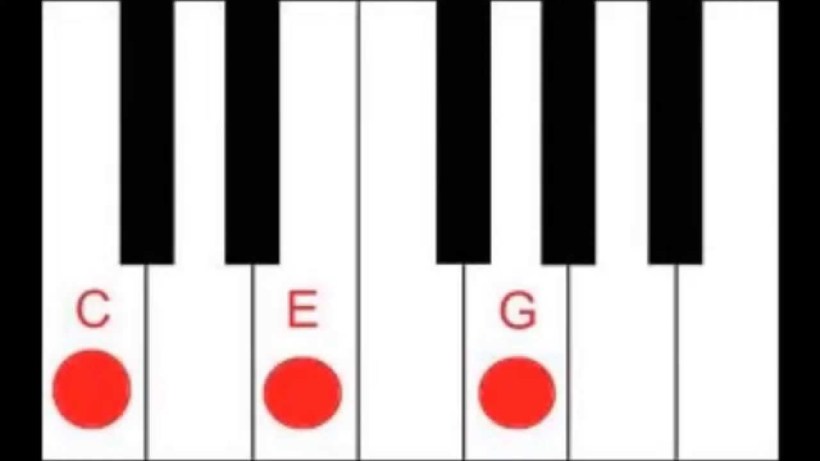

A triad is, as its name implies, a three-note chord. Specifically, it is the kind of chord you get by playing every other white key on a piano.

That’s pretty much literally all there is to it. If you just start from a white key, and play every other note until you have three, you have a triad.

Triads, it turns out, are very very important in music. Unless you listen to a lot of jazz, chances are that almost every chord you hear on your daily listening rounds is some kind of triad. So knowing these things is extremely helpful to understanding music.

How Triads Work

One way to figure out what notes are in a triad is with the handy and memorable mnemonic device “ACEGBDFACE.” That’s right, read that one aloud. “ACEGBDFACE.” Pick any group of three adjacent notes from that list and you’ve got the notes in a triad.

The mathematically minded of you have probably already figured that this means that there are really only 7 unique combinations of triad:

- ACE

- CEG

- EGB

- GBD

- BDF

- DFA

- FAC

Or, if we put them in alphabetical order by the first note:

- ACE

- BDF

- CEG

- DFA

- EGB

- FAC

- GBD

In each of these combinations, we call the first note in the group the “root.” This is the note that the chord is named after–for instance, a “G major” chord has G as its root, and then the other two notes are an B and a D. We call those other two notes the “third” and the “fifth,” respectively. This will be important later.

Now, this particular “spelling” of a triad holds true whether or not any of the notes in the chord are sharp or flat. So, a Gb major chord will have a Bb and and Db chord–not an A# and a C#. Even though A# is the same note as Bb.

This is where you get into the whole concept of “spellings.” Pretty much all the time, you’ve got to make sure that any chord you’re writing is shown on the list above. If you don’t, you have mis-spelled your chord. If this is confusing you at this point, don’t worry about it too much. Just memorize the ACEGBDFACE thing and then try to apply it to your own work. It’s easiest to understand how this works in practice.

How to Name a Triad

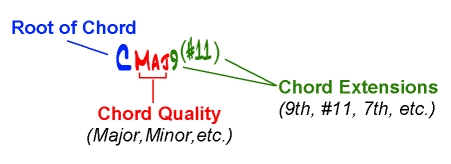

Every triad there is has two components that are important to your average, workaday musician. These are the root and the quality, or type of chord.

Ok, so we’ve been over what the root is above. But just in case you missed it: the root is just the first note in the group of three in a triad, and the one that you name the chord after. But, let’s get to chord quality.

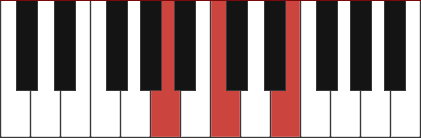

The overwhelming majority of chords that are used in pop, rock, and classical music are one of two qualities: major, or minor. To understand the difference between these two, let’s compare the difference between a C triad on a piano and an A triad:

You may remember from my very first post that the seven notes we use in western music aren’t all the same distance apart. This is the first time this plays out in practice. Count carefully the distance between C, E, and G, and compare that to the distance between A, C, and E.

If you do that, you’ll notice that C and E are further apart (three black and white keys between them) than A and C (two black and white keys between them). That right there is the difference between a major and a minor chord: in a major chord, the third of the chord is one half-step further from the root than in a minor chord. This is why, by the way, it’s called “major.” Major means bigger.

So, if you wanted to name an ACE chord properly, you would call it an “A minor” chord. If you wanted an A major chord, you’d have to bring the third of the chord up a half-step, and write it as A, C#, E.

If you mess with the fifth, you can get two other significantly less common triad types: a diminished triad (which is basically the same as a minor chord except the fifth is one half-step closer to the root) and an augmented triad (which is basically the same as a major chord except the fifth is one half-step further from the root).

Now that you know that, can you figure out the quality of each of the other chords you get by playing every other white key on the piano?

What a Chord Progression Is

Now that you know what a triad is, it’s time to learn what a chord progression is.

A chord progression is just a bunch of chords in a particular order. Tah-dah! That’s literally all it is.

When musicians use that term, they’re usually thinking about chords progressing logically from one to the next–meaning that chords will proceed in a predictable fashion based on the way they usually do. And, like 95% of the time, chords proceed in a very predictable way. Just watch that Axis of Awesome video to see what I mean by that.

Common Chords that Aren’t Triads

So, if at this point you understand what triads are, how they’re named, and how they work, you’re probably wondering what all those other chords out there are. The answer is: a lot. But they pretty much all have triads of some kind as their foundation. So if you have a thorough understanding of how a triad works, what its components are, and so on, you’re going to be able to understand most other chords out there.

I don’t really have space in this post to go into great detail about these other chords, but I will say this: most other chords are named after the notes they add to the chord that aren’t in a triad. So a G dominant 7 chord is going to be a G major triad plus the 7th note up from the root, which in this case is an F. Cadd9 is a C major triad plus the 9th note up from the root, which in this case is a D. I plan on going into greater depth with extended chords at some point in the future. But for now, let’s just focus on triads, and if you’re a beginner, please just focus on the major and minor ones.

Your Assignment for This Week:

Like last time, this week’s assignment contains multiple parts. You can complete one, or two, or all of them, at whatever level of challenge you find appropriate.

Assignment 1: Find a chord progression from a song or piece of music. For each chord in the progression, determine the root, third, and fifth of the chord. If there are extra notes (as you would find in a Cadd9, for example), determine what those extra notes are. If you’re plumb out of ideas for chord progressions to steal, here’s a list of the top 100 most popular songs on Ultimate-Guitar.com. Go find a song, click on it, and steal its chord progression. Easy as pie.

Going to Level 2 in this assignment would be analyzing the chord’s function in the context of the key. For the purposes of this class, we haven’t really talked about key, or function, or whatever, so the only way you’d know about it is from somewhere else. If you don’t know what those things are, then don’t go for this level.

Assignment 2: This is the reverse of assignment 1. Instead of looking at a chord progression, look at a score from Bach, Beethoven, or Mozart (or, you know, someone less obvious) and try to determine the chords being played. My favorite one to do this with was always the Prelude in C major from the Anna Magdalena Bach notebook.

Assignment 3: Using one of the two chord progressions you analyzed above, write a piece of original music. Your piece should be somewhere between 15 seconds and five minutes long.

2 thoughts on “JBT Music Theory Assignment #3: Chords (pt. 1)”