In order to complete this week’s assignment, you’ll need to know the following things:

- What a major scale is

- What is tonic?

- What a “key” is, and how to find out what key you’re in

- How to analyze a melody by scale degree relative to tonic

What a Major Scale is…

As I’ve mentioned, a scale is a collection of notes–often 7–none of which have the same name. There are lots of different types of scale, with different functions and different sounds. For now, we’re going to focus on one of them: the major scale.

A major scale is a collection of notes that follow the familiar pattern outlined in Sound of Music: Do-Re-Mi-Fa-Sol-La-Ti-Do.

If you look at a typical keyboard, and play all the white keys starting on C and count up to 8, you’ll have a major scale.

If you look carefully at the keyboard, you’ll notice that some of the white keys have black keys between them, and some don’t. The reason why that is forms a long and complicated story, so I’m not going to bother going into that too much right now. But for now, that fact is very important, and something you’ll need to memorize. In a C-major scale, every note in the scale is separated by a black key except E & F, and B & C.

Now, if you start counting white keys beginning with C, you’ll find that the black keys go away between the third and fourth, and seventh and eighth notes of a scale.

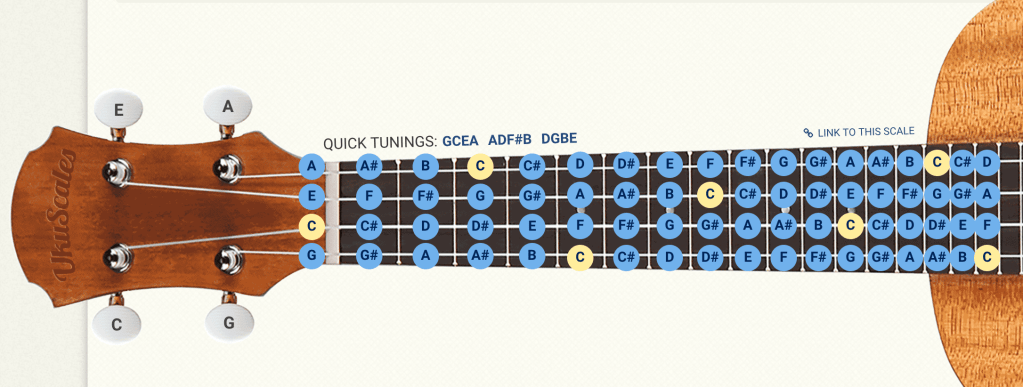

What I’m about to say next is maybe a bit easier to visualize if you looked at it on a ukulele fret board:

The ukulele has all the same notes that a piano does, but you’ll notice that instead of white and black keys it just has frets. Between C and D, for example, there’s a fret for C# (or Db).

If you notice, the notes that have no black key between them on a piano are exactly one fret apart on the ukulele fret board. In music, we say that those notes are a “half step” apart. On the ukulele (and guitar), each fret represents a half step.

Now, if C and C sharp are one half-step apart, and C# and D are one half-step apart, that means C and D are two half-steps apart. And, just like with measuring cups, two half-steps makes one whole step.

So, if you remember the notes of the C-major scale, you’ll also probably be able to figure out the pattern for a major scale:

Whole Step – Whole Step – Half Step – Whole Step – Whole Step – Whole Step – Half Step

I was looking for a handy way to visualize this with an image on Google, but instead I found this video which honestly does a much better job of explaining this concept than I have so far:

Really, the key to the major scale sound is preserving this whole step – half step pattern. If you’ve got a keyboard instrument in front of you and you’ve managed to figure out from the video how to play a major scale starting on every note, you might try messing with the pattern to see what it does to the scale.

For instance, what happens if, instead of playing two whole steps at the start you play three? What about four? It might be fun to experiment just to see what kind of unexpected sounds you can get out of a scale.

The important thing to remember is that pretty much all Western Music Theory as we know it–from Mozart to One Direction–is based on this fundamental concept. The major scale is basically the foundation of our sense of tonality–which is a fancy piece of music jargon I’ll get to in the next section.

What is tonic?

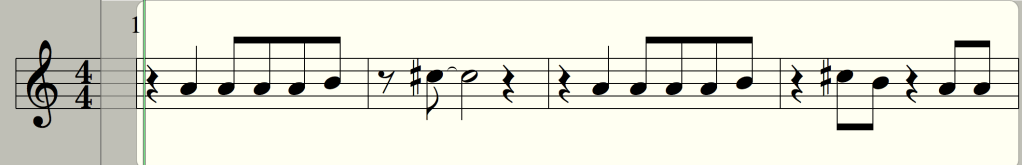

In music theory, we call music “tonal” if it has a strong central note–one that “pulls” the ear in one particular direction and feels as though it is at rest. Describing what that means is pretty difficult without providing examples, so let’s look at a musical example. Here’s a piece of music that my five-year-old became obsessed with last year, which will provide an excellent example:

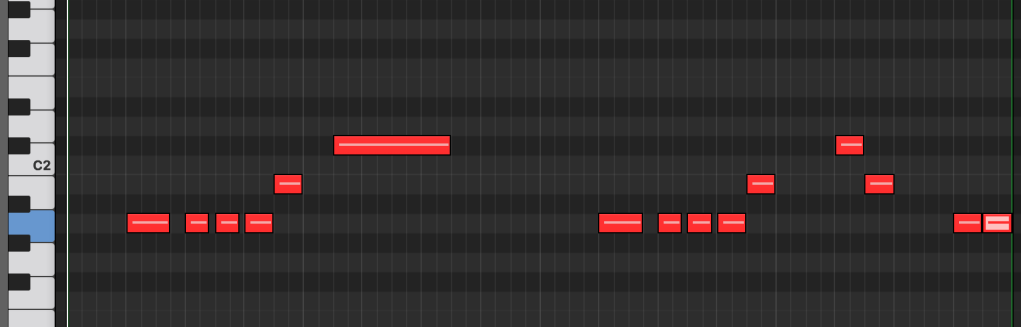

If you listen carefully to this song, and you either have perfect pitch or have an instrument handy, you’ll notice that pretty much everything about it is screaming the note A as a tonal center. At the start of the song, for example, the bass is simply playing an A over and again. In addition, if you look at the keyboard melody, you’ll see that the note “A” plays a pretty strong role, both starting and ending the line:

To get an idea of what tonality means, just imagine Springsteen singing the end of the chorus here (“Even if it’s just danc-ing in the dark”) but leaving off the last word. Not only would the lyrics not make any sense at all, but the melody itself would feel incomplete, as though something was missing. Tonal music demands that the central note–what we call the “tonic,” and in the case of this song, the note “A”–be returned to at the end of a melody. Without that return, it just doesn’t feel quite complete.

Tonal music as we presently understand it began developing in the 16th century, reached its height of complexity and prominence in the 18th or 19th centuries, and is still the foundational style for pretty much all pop music. I mean, not totally all. But, like, almost all.

What a “key” is, and how to find out what key you’re in

Ok, so now that you understand the concept of “tonality,” and understand what “tonic” is, we’re ready to talk about keys. To put it simply, the key of a song is really just stating which note on the keyboard is thought of as tonic, and which notes by extension are considered “legal”–that is, sounding correctly according to the major scale with that tonic.

If somebody says, for instance, that we’re playing a song in Bb major, all you have to do is find the note Bb, count out the whole-step / half-step pattern of a major scale starting from there, and you have all the “legal” notes from that key.

Like, that’s seriously it.

So now you know how to figure out what notes to play if you know what key you’re playing in, but you might be wondering: if I know a song, how do I figure out what key it’s in?

There are two ways to do this, depending on how the melody works. The first is if the melody in question is as obvious about the tonic as Springsteen was with “Dancing in the Dark.” If you can find the tonic note–that is, the note that feels central and feels as though it is “home”–and the song feels major, then voila. You know the key now. Since “Dancing in the Dark” is a major-sounding song, and A is obviously the tonic, that song is in A major.

Another way to do this, though, is to take a look at the melody of a song, and compare that melody to the major scale whole-step / half-step pattern. For instance, the melody of “Dancing in the Dark” starts on an A, and then travels upwards two whole steps. Already, that tells us quite a lot.

But if we listen to the entire song, and take an inventory of all the notes we hear, and then place them in alphabetical order, we’ll end up with the following inventory:

A B C# D E F# G# A

You can sort this out on the piano if you like, but if you count out the steps you’ll find that this does indeed follow the whole-step / half-step pattern of a major scale, starting on the note A.

So here we are! Yet again, we’ve arrived at A major.

For those of you who are more mathematically minded, and have a harder time “feeling” the sense of tonic, taking an inventory of the notes you’re using in a scale is a pretty easy way to figure out the key you’re playing in, as certain keys get eliminated pretty quickly. For example, by the third note of “Dancing in the Dark,” we’ve eliminated every possible key except three.

Before I leave off this topic, I should mention two things: the circle of fifths and minor keys.

First, minor keys: I’m not going to talk about them right now. If you want to learn about them, here’s a useful seven-minute video about it.

Second, the circle of fifths. When I teach music theory class, this is a concept I always spend a lot of time on, and maybe in a future lesson I’ll delve into this tool and how it’s useful more. But for our purposes today, all you need to know is this: every single available major key is shown here in the circle of fifths. If you want to do the process of elimination thing when it comes to finding what key you’re in, you can do the whole-step / half step thing starting on each of the twelve notes below. Or, you can just look at which notes are sharp and which are flat on the diagram below and eliminate keys that way.

How to analyze a melody by scale degree relative to tonic

Ok, so this is pretty much the point we’ve been leading to the whole time. Now that you understand tonality, and key, and can figure out which note you’re playing is the tonic, you’re ready to start analyzing melodies by scale degree!

So, if we go back to our C-major scale, you remember that that scale starts on C, passes through seven notes, and then returns to C again.

C D E F G A B C

If we call the tonic note–which in this case is “C”–the first note in the scale, we can then give each note a number as well as a letter name. So, C is 1, D is 2, E is 3, and so on.

So now we’ve got a scale that looks like this:

| C | D | E | F | G | A | B | C |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 1 |

The term “scale degree” refers to the number that each note gets in the scale. So the scale degree for D is 2. The scale degree for B is 7. Once you’ve figured out the key and the scale, it’s pretty darn easy to figure this out.

It can be really handy to think of scales this way. When you learn a new song, you can start to think of all the notes in the song as being parts of a scale as opposed to randomly assigned notes, and musical patterns begin to emerge very, very quickly.

Take, for example, the Springsteen song from above. Since we’re in A major, our scale degree chart looks like this:

| A | B | C# | D | E | F# | G# | A |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 1 |

The melody for Dancing in the Dark begins with A, B, and C#, or scale degrees 1, 2, and 3. Once I’ve figured that out, I can then play this song in just about every key pretty easily just by learning the first three notes in every scale. Additionally, once I’ve figured that out, I can then understand that “Dancing in the Dark” and “Frere Jacques” have basically the same melody. Also “Three Blind Mice.” And “What Makes You Beautiful.” And, well. You get the idea.

Your Homework…

This week’s assignment is to write a piece of music with a major-scale melody. You have three choices:

- LEVEL 1: Write your melody in the key of C-major, and analyze your melody by scale degrees relative to tonic.

- LEVEL 2: Write your melody in some other key that isn’t C-major, and analyze your melody by scale degrees relative to tonic.

- LEVEL 3: Transcribe a major key melody from a song you know, analyzing the notes by scale degree relative to the tonic.

You can do any of the above or all of the above–however you want to do it! I’m looking forward to hearing what you’ve got!

2 thoughts on “JBT Music Theory Assignment #4: Major Scales pt. 1”