In order to do this week’s lesson, here’s what you’ll need to know:

- What a pentatonic scale is

- How to analyze a pentatonic melody

- How to find the difference between the major and minor pentatonic scales

What a Pentatonic Scale Is

If you’ve never heard the term “pentatonic” before, you’re in reasonably good company…

So, if you’re reading this and you already know what a pentatonic scale is, congratulations! You already know more music theory than J-Lo. That and $5 will get you a cup of coffee somewhere.

Now, if you’re one of the folks who doesn’t know what a pentatonic scale (and maybe, just maybe, J-Lo is reading this now?), let’s go back and explain. As you hopefully remember from Lesson #1, there are seven notes in the musical alphabet, and when those notes are arranged in alphabetical order you get a scale. And as you hopefully remember from Lesson #4, those notes can be arranged into a major scale using a particular whole step / half step pattern. Specifically, that pattern is: Whole – Whole – Half – Whole – Whole – Whole – Half.

When notes are arranged according to that pattern, one of them starts to sound to us like a tonic, or central “home base” that the melody will always return to.

So, having established all that, let’s talk specifically about the pentatonic scale. If you took a Geometry class at some point in your life, you probably are already aware that the prefix “penta-” means five of something. And if you are some kind of evil genius, you probably already know that the suffix “-tonic” refers to “tones” or “notes” or “pitches.” Thus, a pentatonic scale is a scale with five pitches.

So which pitches?

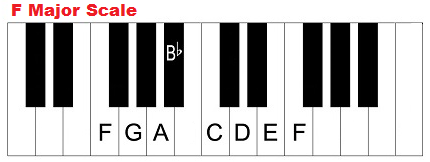

In order to figure that out, let’s go ahead and take a look at the major scale:

Above, we’re looking at the F major scale. And, again, as you hopefully remember from last time, we can think of the notes of this scale as being numbered: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1. And again, Whole – Whole – Half – Whole – Whole – Whole – Half.

Now, the thing that the pentatonic scale does that makes it so useful to so many people, and so universally used amongst folk cultures, is it takes away all the dissonant notes.* Or, to speak a bit more specifically, it removes all the notes that are a half-step away from one of the main notes in the scale.

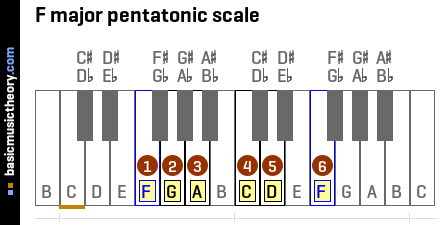

When you’re looking at a major scale, what this means is that you take away notes 4 and 7 from the scale, and then voila. You have a pentatonic scale:

Now, notice the way this scale pattern now works. In all the spots in the scale where we used to have half-steps, now we have gaps. So our scale pattern now looks like:

Whole – Whole – (Whole + Half) – Whole – (Whole + Half)

In case that notation is confusing, I’m just trying to point out that now, in the pentatonic scale, where there were steps, there are now skips. Since we’re not using every note in the musical alphabet, the pentatonic scale is inherently a disjunct scale. (Remember that fancy word? It’s a good word.)

Of course, the pentatonic scale is so universally used in popular music that oftentimes it won’t feel to you like you’re skipping a note when you make that leap from the third to the fourth note in the scale. It’ll just feel natural. So much so, in fact, that Bobby McFerrin can get an audience to perform the scale with no prior training, instruction, or rehearsal. They just know it:

This means that you probably already know it, too. And so does J-Lo–even if she’d never heard the word “pentatonic” before in her life.

How to Analyze a Pentatonic Melody

In the previous lesson, we discussed how to number the notes in a musical scale. The tonic note gets called 1, and then each subsequent note gets a sequential number after that, in a way that actually makes a ton of sense and is hopefully intuitive.

With the pentatonic scale, you can number the notes accordingly, in the way that the image above did. If we’re looking at the F pentatonic scale, you could count the notes like this:

| F | G | A | C | D | F |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 |

This does a great job of really driving home that a pentatonic scale is a five-note scale. But, for reasons that will hopefully become apparent at some point in the future, it’s a potentially confusing way to think about the scale.

To put it in the simplest terms possible, when I’m numbering the notes of the pentatonic scale I like to account for the notes that were skipped: numbers 4 and 7. So that F (major–more about this later) scale should actually be numbered accordingly:

| F | G | A | C | D | F |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 1 |

So you see how I did that?

Now, you try. Build some pentatonic scales from some major scales. Take away the fourth and the seventh note in the scale, and there you go!

How to Find the Difference Between the Major and Minor Pentatonic Scales

As I mentioned above, so far we’ve only been talking about the major pentatonic scale–which, sensibly, is derived from a major scale. But what about the minor pentatonic scale?

Well, the truth is that they’re actually the exact same thing. Or, to be more precise, they’re two different modes of the exact same thing.

To drive that point home, here’s a pentatonic melody I came up with, just now:

That melody, by the way, looks like this:

What happens, though, if we add some chordal instruments in the background with that exact same melody? Here’s a version where I’ve added a piano playing an F-major triad, along with a bass synth (forgive the low-effort sounds, here folks) playing a simple rhythmic accompaniment on an F:

As I hope you can clearly hear, that melody sounds strongly major, and has a strong feeling of “F” being our home note.

Now, what if we change the context? What if, instead of playing an F major in the background, we play a D minor?

Again, as I hope is apparent to your ears, the melody suddenly sounds completely different–even though it is exactly the same melody! What once sounded like something clearly major with F as a tonic note now sounds like a minor scale, with D as the tonic note.

Cool, isn’t it?

To generalize this, the rule for the relationship between the major pentatonic and the minor pentatonic scale is that they’re the exact same scale, it’s just we’re thinking of a different note as tonic. To make your major pentatonic scale minor, just change the tonic note to note 6–and keep all the notes the same.

So our F-major pentatonic scale above:

| F | G | A | C | D | F |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 1 |

Can become a D-minor pentatonic scale simply by making note #6 (D) into note #1 and keeping all the other notes the same. Just remember to take the notes you skipped into account:

| D | F | G | A | C | D |

| 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 1 |

Assignment for This lesson:

Create a piece of original music at least 8 measures in length that utilizes the notes of the pentatonic scale. You can use either a major or a minor pentatonic scale, but make sure you identify:

- The root note of the scale you’re using

- The scale degree numbers of each pitch you’ve utilized in crafting your melody

Pentatonic melodies are always super fun, so I’m looking forward to hearing what you produce!

*The notes used in the pentatonic scale also happen to line up very well with the first notes in the overtone series. But more on that in a future lesson.

One thought on “JBT Music Theory Lesson #5 – The Pentatonic Scale”