What You Need to Know to Complete this Lesson:

In order to complete this lesson, you’re going to need to know the following stuff:

- How to figure out what key a piece of music is in

- How to deal with triads

- What a chord progression is

- How to analyze a chord progression using Roman Numerals

- What are some common chord progressions, using Roman Numerals?

As you may have noticed, two of the four things you need to know for this lesson are covered pretty extensively in previous lessons–so if you feel iffy about those concepts, check out the lessons again! I’m not going to cover them again here.

What a Chord Progression Is

I’ve been asked a lot in my career as a music educator what a chord progression is. Like, what’s the difference between the chords of a song and its chord progression?

The best answer to this question that I could figure is that the term chord progression refers to a group of chords that follow each other, one after the other. And though that definition is technically correct, it doesn’t quite encompass an important element of a progression: namely, this concept of progress. When you progress from one thing to another, you are traveling in a particular forward direction, towards some sort of goal.

So, to be a bit more specific: a chord progression is a group of chords that follow one another and create a sense of forward motion towards a specific goal.

Now, in tonal music–that is, music that has a strong sense of a single note being tonic–a chord progression typically brings you forward from a tonic to a thing that isn’t the tonic, and then back to the tonic again. Music in the Western Tradition has been observing this basic form for like a thousand years in one way or another.

In fact, medieval music theorists thought of this progression as being symbolic of the human progress, starting one with God, moving away, and then returning to God.

Kinda neat concept when you think of that way.

How to Analyze a Chord Progression Using Roman Numerals

Ok, so now that you have a basic idea of what a chord progression is, we need to think about how to analyze a chord progression. This is the part of the lesson that is going to build pretty heavily on the prior lessons referenced above (Lesson #3 and Lesson #4, specifically), so if you feel at all shaky with the content covered in those lessons you gotta go check them out.

Ok, so if you now feel super comfortable with building triads and dealing with the major scale, we can start to think about Roman Numerals. As you remember, when dealing with a major scale, we think of the central note or “tonic note” in the major scale as being number 1, and all the other notes in the scale being numbered sequentially following that one. So, if we’re operating in the key of F major, F would be 1, and all the other notes in the scale would be numbered like so:

| F | G | A | Bb | C | D | E |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

As you remember from the first chords lesson, each one of those notes can be the root of a triad, each of which has its 3rd and 5th. If we go ahead and build chords off each of those notes, we’ve got the following:

| 5th | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| 3rd | A | Bb | C | D | E | F | G |

| Root | F | G | A | Bb | C | D | E |

| Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

Of course, when we’re talking about analyzing music, music theorists feel a pretty strong need to distinguish between times when you’re talking about single notes (like, in a melody or bass line) and when you’re talking about chords. Like, when we say “that’s a one” we need to know from our notation whether we’re talking about a chord or a note.

So that’s why, in music theory, when we’re talking about notes we use regular numbers, and when we’re talking about chords we use Roman Numerals. So, if I’m being accurate, the table above should actually look like this:

| 5th | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| 3rd | A | Bb | C | D | E | F | G |

| Root | F | G | A | Bb | C | D | E |

| Number | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII |

Get it? It’s actually simpler than you probably thought it was, if you’ve never done this before.

The thing is, there’s actually more information we could include in the chart above, because as long as we’re in a major key, all of these chords have a specific quality–remember what that means?

If you’re the kind of person who likes to figure things out on your own, go ahead and look at each of the chords above, and try and figure out whether they’re major or minor. I’ll wait here while you figure it out.

If you’re not the kind of person who likes to figure things out on your own, here’s the answer:

| 5th | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| 3rd | A | Bb | C | D | E | F | G |

| Root | F | G | A | Bb | C | D | E |

| Number | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII |

| Quality | Major | Minor | Minor | Major | Major | Minor | Dim |

So there we go. In any major key, chords I, IV and V are major; II, III, and VI are minor; and VII is diminished.

Having gone this far, I know my college theory teachers would hate that I’ve ignored one convention with Roman Numerals: capitalization. Typically, in classical music theory, we use capital Roman Numerals for major chords, and lower case for minor or diminished chords.

So if I’m being really accurate to what my teachers taught me, my chart should look like this:

| 5th | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| 3rd | A | Bb | C | D | E | F | G |

| Root | F | G | A | Bb | C | D | E |

| Number | I | ii | iii | IV | V | vi | vii |

| Quality | Major | Minor | Minor | Major | Major | Minor | Dim |

In my career as a musician, I’ve seen people use lower case and upper case Roman Numerals, to be honest–so it’s not that important to me as a teacher that my students replicate any particular system exactly as long as they understand what’s basically going on.

What Are Some Common Chord Progressions, Using Roman Numerals?

Ok, so now that you understand how to do Roman Numerals, and now that you understand the basic patterns of how Roman Numerals work in a major scale, we can start talking about the “why” behind this whole thing.

Music, at bottom, is really just a bunch of interlocking patterns that are used over and over again–in kind of the same way that language is a bunch of interlocking patterns. The whole point of learning Music Theory, in my opinion, is simply to familiarize yourself with what those patterns are. That’s why I love teaching it, and that’s why I think it can be so powerful. The better you know the patterns, the less difficult learning new music becomes.

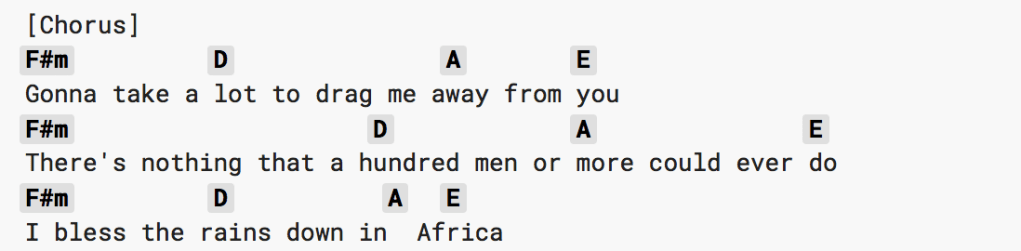

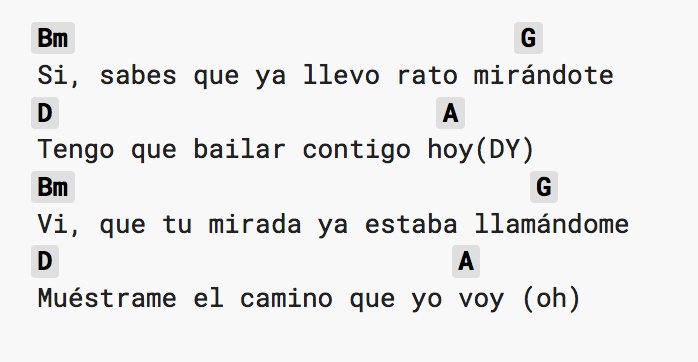

So, why do we need to know Roman numerals? Because they help us generalize chord progressions across keys. For example here are the chords for two songs: the chorus of Africa by Toto and Despacito by Luis Fonsi:

So these are two completely different songs in completely different keys, but if we generalize their progressions, we can find a pretty deep similarity.

First, let’s take a look at Toto. It might not be obvious to you, but the tonal center in that song (if we consider it to be a major key) is A. And the Roman Numeral chart for the key of A major is:

| 5th | E | F# | G# | A | B | C# | D |

| 3rd | C# | D | E | F# | G# | A | B |

| Root | A | B | C# | D | E | F# | G# |

| Number | I | ii | iii | IV | V | vi | vii |

| Quality | Major | Minor | Minor | Major | Major | Minor | Dim |

So the Roman Numeral analysis for “Africa” is: vi – IV – I – V.

“Despacito” is obviously in a different key–and rather than make you hunt for it, I’ll tell you: it’s in D major (or B minor). Thus, “Despacito’s” Roman Numeral Progression of Bm – G – D – A is… vi – IV – I – V! The exact same!

I’m not the first person to notice this phenomenon–but you should know that it goes far deeper than simply pop music of the last forty years. Chord progressions have been working basically this way in Western Music since at least the 17th century.

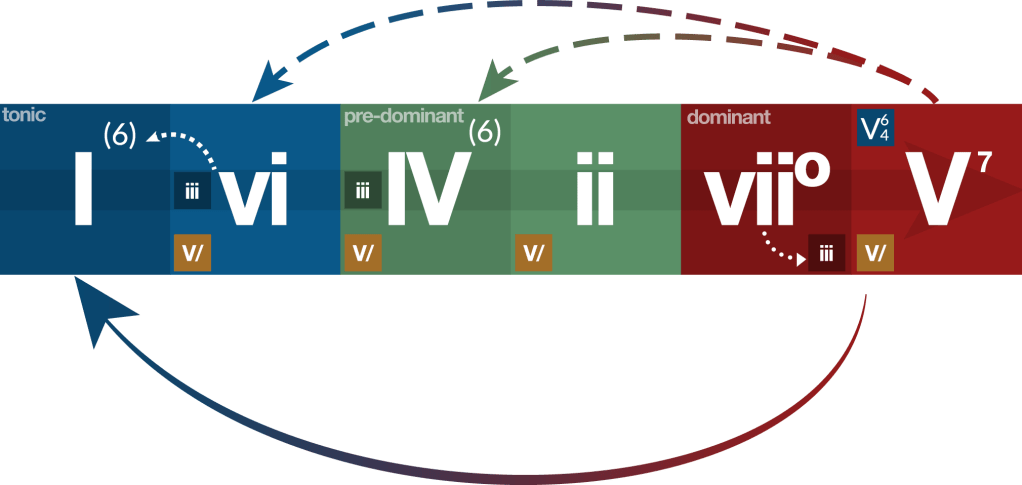

Around that time in Europe, composers and theorists began thinking of chords as having specific functions. In tonal music, there was “home”–which meant, tonic, or 1 or I–and there were chords that took you on a journey away from home. Specifically, my college theory professors would always draw a diagram like this when trying to explain this idea:

Overall, the I chord is “home,” and creates a feeling of being “at rest.” The V chord is “away from home,” and creates a feeling of tension that “wants” resolution, or a return to I. To a lesser extent, the vii chord works the same way. Sometimes, a song or composition will just go straight to the V to create some tension that then gets immediately resolved, but most of the time a composer will stick in a “pre-dominant” chord–or a ii or IV–that sets the expectation that it will be followed by a V that will then return to I.

This pattern, of tension created by a V chord followed by resolution to a I chord, is one that began being common in European music in the 16th century and honestly continues to be quite widespread all over the world 500 years later. Though some small things have changed, I’d be willing to bet that if you conducted a Roman Numeral analysis of all the songs you listen to on a daily basis, at least half of them would obey that basic rule in one way or another.

Assignment for this lesson:

This lesson’s assignment is a two-parter. Since Roman numerals are really talking about two distinct skills–analyzing existing music and creating original music–this assignment is going to cover both those skills. So, here we go:

- Part 1 of this assignment is to pick a song that you know reasonably well, and either find the chords (on a site like ultimateguitar.com) or figure them out by ear. Having done that, use your knowledge about determining the key of a piece to do a Roman Numeral analysis of the chord progression of that song.

- Part 2 of this assignment involves my favorite compositional technique: stealing! Having figured out the Roman Numerals of the song you chose for Part 1, steal that progression and write a brand new melody to go along with it. Then, voila! You have a new composition. Share that composition in the comments for this lesson!

One thought on “JBT Music Theory – Lesson #6: Chords pt. 2”