So I ran a poll on the sub-reddit, and this is what the people wanted! So here it is.

So here’s what you’re gonna need to know in order to complete this lesson:

- What “harmony” means

- Using common Roman Numeral progressions

- How to use triads

- How to build melodies using scales

- What counterpoint is and why it matters

- What Intervals Are, and How to Name Them

- Dissonance and Consonance

- The different types of contrapuntal motion, and what effect they have

As you may have already noticed, some of these things refer to previous lessons. If you haven’t done those, go check ’em out now. Below, I’m only going to focus on what’s new.

What “Harmony” Means

Harmony is a super tricky word, because in music we use it a lot to refer to different things. If you’re talking about music theory, you might be talking about the chords in a song. You might also be talking about a specific analysis of the notes sounding simultaneously in a given chord. Or you might be talking about someone singing a background part that’s meant to blend with a melody (e.g., “singing a harmony”). Sometimes, in some genres of music, someone might even mean something very specific when they call a part a “harmony.”

Ok, so to try to clear up that confusion, let’s narrow things down. For the purposes of this lesson, we’re going to refer to “harmony” as a secondary melodic part, that is meant to accompany the main melody and that “fits” with that main melody. The rest of the bullet points in this lesson are going to be talking about how to do that.

Write a piece of original music that has at least two melody voices that are “singing” in harmony. This means that each voice has at least some melodic interest–not just a melody + accompaniment type situation. You can add extra voices if you like—or extra accompaniment if that’s something you want–but you must have those two voices at minimum.

What counterpoint is and why it matters

I was struggling to express a definition for counterpoint, so I just googled it. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, this is what counterpoint is:

Counterpoint, art of combining different melodic lines in a musical composition. It is among the characteristic elements of Western musical practice.

–Encyclopedia Britannica

So, there you go. That’s what it is–the art of combining different melodic lines in a musical composition. Counterpoint first started to become important to Western music back in the middle ages, when a new musical style called “polyphony” started to become common in church music.

Instead of having everyone in church sing the melodies of hymns at the same time, or singing parallel harmonies a fourth or a fifth above the melody, in polyphonic music every singer sings a unique melody. The technical challenges of making this kind of music sound good gave rise to a whole new music theory and a set of rules that would eventually be codified (in 1725) by a guy named Fux (the “u” is pronounced as “oo” and not “uh” for what I hope are obvious high-school-teacher-related reasons) in a book called Gradus ad Parnassum.

This book articulates a number of rules for how to write polyphonic music. A lot of these rules (e.g., the infamous “no parallel fifths”) are still taught in music theory classes today–in fact, I’ve done a lot of it. You really can’t get past Music Theory 101 in most American universities without learning at least some of the rules Fux laid out almost three hundred years ago.

The antiquity of Fux’s work actually goes back further than that, as the music he was using as inspiration was composed more than 160 years earlier by Giovanni Perluigi da Palestrina–who he mentions several times as being the greatest musical master ever to live. By the time Gradus ad Parnassum was published it had been at least 100 years since anyone composed any new music in the style of Palestrina. So, it was a little out-of-date even when it was published.

If you get nothing else out of this section, though, I hope you at least give Palestrina’s music a listen. It is truly beautiful.

So that’s what counterpoint is. But why does it matter?

Well, the answer is that it kind of doesn’t. Counterpoint in the style of Fux, or Bach, or Beethoven has very little bearing on modern music making. Or about as much as the ways that Romans built roads has on the creation of the hyperloop.

This isn’t to say that it isn’t cool, or that it isn’t worth learning, or that learning it won’t make you a better musician. Learning arcane and difficult-to-follow rules absolutely will make you a more skilled musician. But you can do that in all kinds of ways, and you need to ask yourself if you’re interested enough in the musical style of people who’ve been dead since before the United States existed to spend the time rigorously learning it. If the answer is yes: GO FOR IT!! But you’re not less of a musician if you just ignore every counterpoint rule that existed and simply make music that sounds good to you.

All this being said, there is one concept that these long-dead composers understood quite well that will help you a lot: how to handle dissonance and consonance.

What Intervals Are, and How to Name Them

So, you see, I’ve gotten this far into all of this before I realized that I haven’t yet talked about intervals on this whole thing. I’m going to have to do that next time, because it’s pretty important to understanding this lesson. But it’s a whole thing, and if I were planning this as a unit I definitely would want to spend at least a few days covering intervals before we’d gotten to this point.

Shit.

Well, I’m going to set that aside. I’ve thought now that it would be good to include a separate section that talks about what intervals are, but instead I’m just going to say this: “interval” refers to the space between any two notes. We measure intervals starting at the lower pitch and counting upwards, usually.*

Intervals have two bits of information in each of their name: a type (major, minor) and a number (1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc.). We’re not going to worry too much about the type for now. To get the number, though, all you need to do is count letter names of notes. So, for example, if you’re trying to figure out the interval between C and E, you would begin at C (which we’re going to call number 1), and count letter names until you get to E.

If you did it right, you should get “3.” The interval between C and E is a third. This is true whether the C is Cb or C#, or whether the E is Eb or E#. The interval between any note with the letter name C and any note with the letter name E is a third.

So, if we lay out all the notes of a C major scale, here are the possible intervals we get, compared to a C as the lower note:

| C | D | E | F | G | A | B | C |

| Unison | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | Octave |

Dissonance and Consonance

So, I’ve been saying all this stuff as a way to get to the concepts of dissonance and consonance. On a basic level, those two words simply mean “sound bad” and “sound good”–dissonance comes when you play two notes simultaneously that don’t sound so good together, and consonance happens when you do the opposite.

If you read Fux’s book, you’ll notice that he spends a good amount of time defining these words in terms of intervals. Some intervals sound bad (2nds, 4ths, and 7ths) and other intervals sound good (3rds and 6ths) or really good (5ths and octaves). Using a metaphor of closeness to Godliness, he called the really good intervals “perfect” consonances (because what could be more perfect than God?), and the still-good-but-less-so intervals “imperfect” consonances.

If you play around with these intervals on a keyboard, you might find yourself rediscovering some of what Fux already said, because a lot of what makes notes sound good or bad together has to do with nature and how our brains perceive things.

So why is this important to writing harmonies?

When you’re writing harmonies, you need to understand this concept. Dissonant intervals don’t necessarily need to be avoided, but they do need to be treated with care. If you want your harmony part to sound nice and pleasant, keep away from the dissonant intervals as much as possible. If you want it to sound jarring and unsettled, use as much dissonance as you can.

Another concept to keep in mind is the idea of tension and resolution. Because of their nature, dissonant intervals often feel quite tense. So if you follow a dissonant interval with a consonant one, it can create a rather pleasing sense of tension and resolution.

Fux had a bunch of ideas about how to handle these things that nowadays are quite outdated. But learning about them can be helpful if you want to hone your skills at writing harmony. If you’re one of those overachieving students that everyone hates but wishes they were more like, please read the PDF I linked to above so you can learn more about this!

The Different Types of Contrapuntal Motion, and What Effect They Have

I hope now that if we’ve made it this far, you understand that melody involves notes in motion. In case you’re at all confused about this, go check out lesson #1 again where we talk about melodic contour.

When you’ve got two melodies happening simultaneously, you’ve got a whole other range of possibilities that open up. Now, not only do you have to consider how your melody moves, but also how that second, simultaneous melody moves along with it.

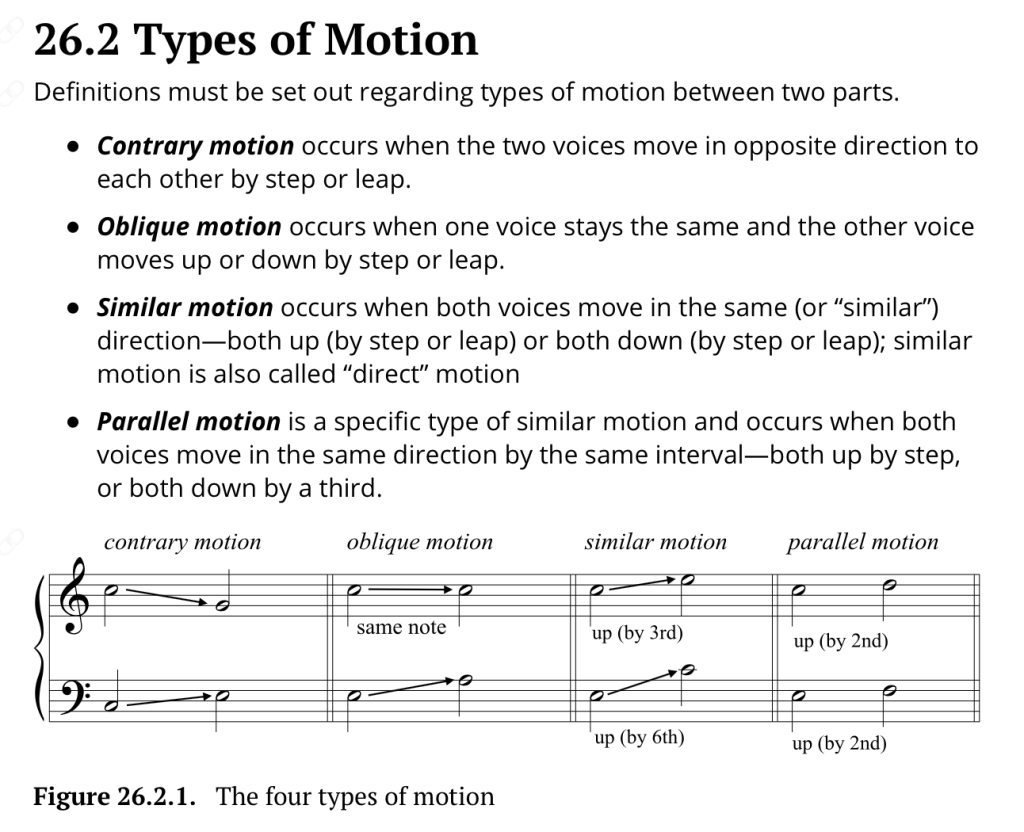

When two melodies are occurring at the same time, there are a few ways we can think about their motion (I’ve screenshotted this bit from here, go check out the original!):

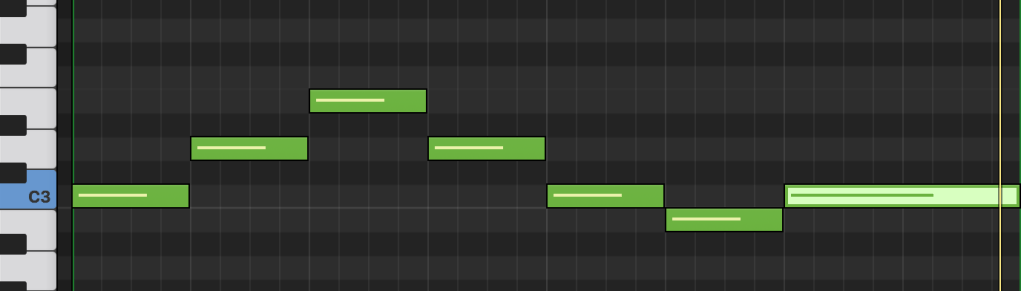

To give you a sense of what each of these mean and what they sound like, here’s an example. We’ll begin with a really painfully simple melody:

In other words, in the key of C major this melody is going “Do Re Mi Re Do Ti Do” in a pretty straightforward, simple rhythm. Before you press play on the sound file below, try and sing that melody to yourself. See if you can hear it in your mind’s… ear?

Now go ahead and press play on this file:

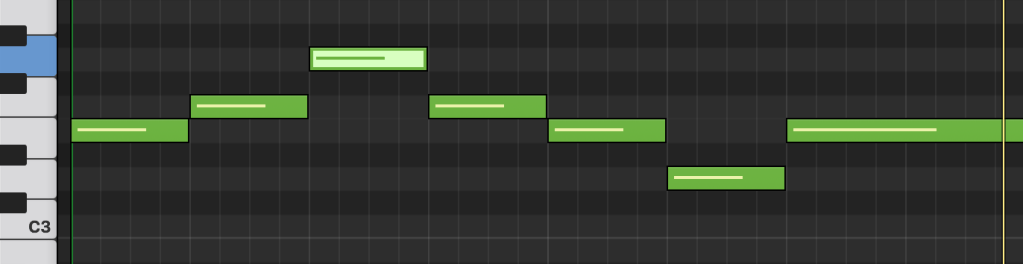

Now we’re going to try to write a harmony to this melody using each of the types of motion demonstrated above. We’re going to begin with what, in my opinion, is the easiest type of motion to make sound good, which is parallel motion. In music, two voices moving in parallel are voices that are moving in the exact same direction and amount, but starting in different places. If you’re ever trying to figure out a harmony part to a melody, parallel 3rds or 6ths are pretty much always going to be a winner: no matter what, they’ll sound good.

To write a harmony in parallel 3rds, all you really need to do is copy and paste the melody you’ve written, move it up three steps, and then make sure to move around the notes so that they’re all in the right key (e.g., when I copied and pasted the melody and moved it up so that it’s starting a third above the original melody, I needed to change the F# and G# to F and G natural, respectively, in order for it to work).

Having gone through those steps, my parallel third harmony now looks like this:

Or, as you can hopefully see, it’s Mi-Fa-Sol-Fa-Mi-Re-Mi in the key of C major.

Again, before you hit play on this, try and sing this harmony to yourself.

As I’ve said, a parallel 3rd harmony is pretty much always going to be a winner. Here’s what they sound like together:

If you listen carefully to that, I hope you can hear that while this harmony sounds pretty solidly good, if your goal was to write a harmony line that retains some independence from the original melody, all that parallel motion isn’t really getting the job done. Instead of sounding like two different parts, they’re starting to blend together into one because they’re so similar to one another. Do you hear it that way? Yes? No? Either way, let me know somehow.

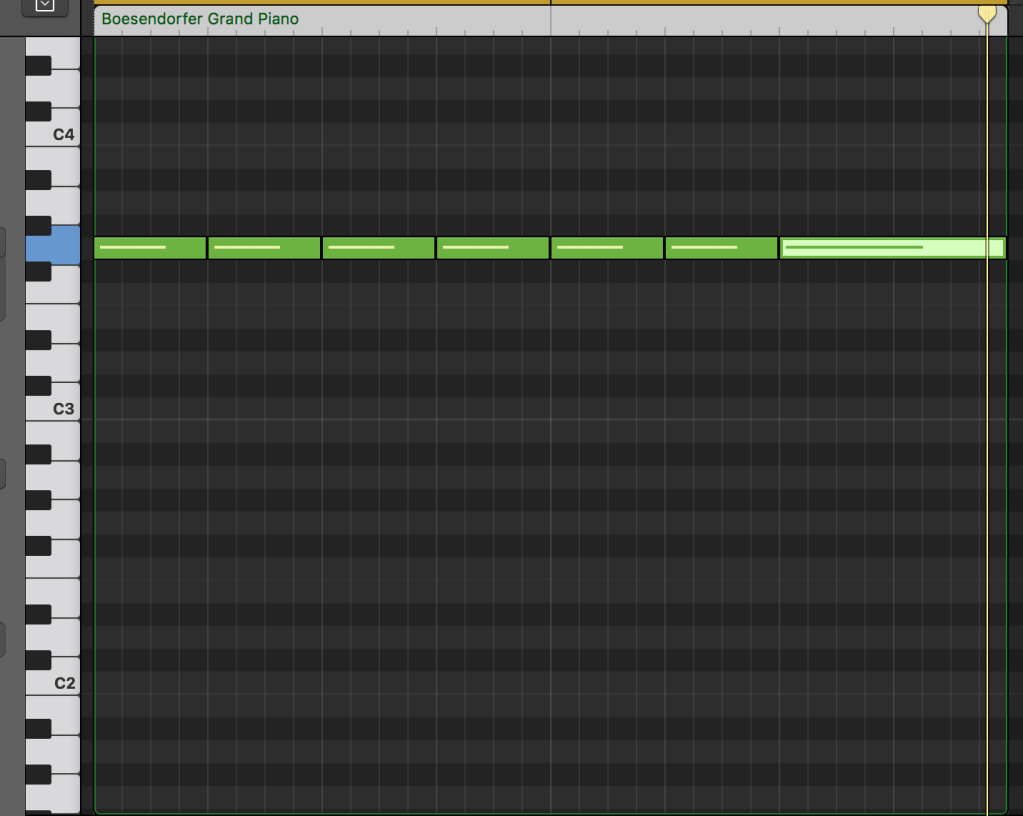

Ok, moving right along, let’s get to the next easiest type of motion to handle: oblique. Oblique motion is what happens when one of our two voices isn’t moving at all and the other is moving up or down.

Usually, if I’m harmonizing something this way, I would choose a note that’s gonna sound good no matter what’s going on in the melody or the harmony. This means choosing a tone that fits with the chord (see that lesson on building chords). In this case, I’m gonna write a harmony that is just a repetition of the 5th note of the scale, G:

And as boring as it looks is exactly as boring as it sounds…

By itself, this harmony is nothing special to listen to. But I always think that matching a static line like this one against one that moves can sound really cool, lending a thickness to your harmonic texture that you don’t get from the parallel harmony above:

Moving right along, the third type of motion we’re going to talk about in this lesson is contrary motion. Just like your contrary friend, who always does the opposite of what everyone else is doing, a harmony line moving in contrary motion is simply doing the opposite of whatever the melody is doing. Melody goes up? Well, then the harmony goes down. Melody goes down? Harmony goes up. I hope you get the picture.

To write a contrary harmony to the melody I wrote above, I did this (and I’m including the melody so you can see a little bit better what’s going on):

As you can, both lines begin on the note C, but wherever the melody goes up, the harmony goes down–and vice versa. Put together these two things sound like this:

As I hope you can hear, having two voices moving in contrary motion makes them sound even more independent from one another than oblique motion does. To my ear, the above harmony sounds almost more like two completely separate voices than it does a true melody / harmony situation.

As you’ve probably noticed, I’ve presented these three types of motion in increasing independence order. Parallel motion creates a primarily blended effect; oblique motion creates a little more independence and thickness in your texture; contrary motion creates a feeling of almost total independence.

Now, there are tons of rules of thumb that go along with writing two-part harmonies effectively. Like, literally tons of them, and I could talk about it at great length. But I’m not gonna.

At least not right now.

The Overall Rules of Thumb

So now that we’ve gotten this far, and I want to thank you for bearing with me while I tie myself into knots trying to figure out how to explain all these concepts, you’re probably wondering how to put all these pieces together.

Generally speaking, when you’re writing harmony in two voices, you need to keep track of:

- Making both your melody and your harmony reasonably melodic

- Making sure both your melody and your harmony fit with the underlying chord progression you’ve chosen for your song, or at least that they’re not too dissonant

- That you’re using a nice blend of dissonant moments that then resolve peacefully to consonant moments

- That you’re focusing on using different types of motion (similar, parallel, oblique, contrary) and understanding the effect each has on the listener

- That your harmonies aren’t clashing with anything else you’ve got going on in your composition.

That seems like a lot, and, well, to be honest it is. But with practice you get better at this sort of thing, and if you do enough harmonizing, you’ll eventually realize that there are a relatively small number of patterns that repeat frequently in music that we like to listen to. The only way to really internalize those patterns, though, is to do it over, and over, and over again.

So what better time to start than with this assignment!

Your Assignment for this Lesson…

For this lesson, compose a piece of music with two distinct voices that are in harmony with one another. Don’t worry too much about creating independence if you don’t want–just write two parts that fit together.

Good luck!