Here’s what you need to know for this lesson:

- How Scales Work (Lesson #1)

- What the Major Scale is (Lesson #4)

- How Chords Work (Lesson #5)

- What a minor key is and where it comes from

- The difference between “parallel” and “relative” minor keys

- The three different minor scales and why they exist

What a Minor Key is and Where It Comes From

As you may remember from the chords lesson, the 3rd of any chord is really, really important. It is the difference between a major sound and a minor sound in a chord, and just simply moving that one note down a half-step from the major can completely change how the whole chord sounds.

Well, it really isn’t any different when it comes to a scale. If you take the third note of a major scale and scoot it down a half step, you’re going to get some kind of minor-sounding scale, even if you don’t change anything else about the scale. Wow. Cool isn’t it?

If you don’t believe me, go ahead and try it! On the embedded MIDI keyboard below, try playing all the white keys in order, starting and ending on C. (This cool keyboard code from this link!) Then, try and play the same scale, but instead of playing E, just play Eb. Hear the difference, even with all the other notes remaining unchanged?

*Note: If you’re struggling to find C on this keyboard, check out this image. Have it open while you’re playing with the keyboard above.

Of course, just changing that one note doesn’t really give you what we now call a “natural” minor scale. In order to get that–at least, in order to get what we’ve been calling that in Western Music for the last ~400 years–you need to lower the third note, the sixth note, and the seventh note of the scale. If we’re trying to build the C natural minor scale, that means we’re going to play Eb, Ab, and Bb instead of E, A, and B.

That sounds, incidentally, like this:

The reason why we call this particular scale the “natural” minor scale brings me to our next topic…

The Difference Between “Parallel” and “Relative” minor keys

OK, if you’ve been to music class before or spent time with folks who went to music school, you may have heard the term “relative” minor. This particular term has nearly everything to do with why we call the scale I gave above the “natural” minor scale.

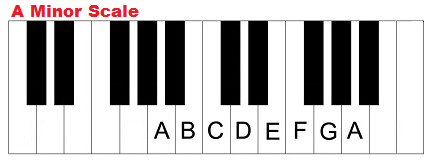

So, let’s say that for some reason you wanted to play all the white keys of a piano, but instead of starting and ending on the note C, you wanted to start and end on the note A. You’ll notice if you play that scale on the keyboard above, that it sounds pretty… minor. If you take a look at the notes of that scale, and carefully count the spaces between the third, sixth, and seventh notes of the scale that they’re exactly the same as the natural minor scale.

Whoa.

So, this demonstrates a rule that holds true of any key. If you play the notes in any key starting on the sixth note of the scale instead of the first, you’ll get a natural minor scale. Which is why we say that (for example) A minor is the “relative minor” of C major–because the A natural minor scale has the exact same notes as the C major scale, just starting in a different place.

If you check out the circle of fifths, and try out the rule above, you’ll notice that it holds for every single key:

In the heading here, I mentioned that I would say something about “relative minor” and “parallel minor.” I hope by now you already have some sense of what the first of those two phrases is talking about. The second, parallel minor, is referring to a minor key with the same tonic. So, if C minor is the parallel minor key of C major. D minor is the parallel minor key of… you guessed it! D major.

Got it? Good.

The Three Different Minor Scales and Why They Exist

Ok, so now that we have some idea what the natural minor scale is, where it comes from, and how to use terms like “relative” and “parallel” minor keys, it’s time to start thinking about some weird stuff that happens when we’re talking about minor keys. This weird stuff is why there are three minor scales that classical musicians have to memorize and practice, in addition to all the other stuff they have to memorize and practice.

So, to understand this, let’s begin by looking at a pretty basic major key melody–one that goes E-D-C-B-C (or 3-2-1-7-1, to generalize it across keys), a pretty common melody that is often used at the ends of phrases, even today. Since I have two hands and I like to use them both on the piano, I’ll go ahead and play the left-hand chords using the simplest and most obvious options available: C-G-C-G-C, or I-V-I-V-I. Here’s what that sounds like:

Now, one of my favorite things in the world to do is change major key melodies into minor key ones. If we shift this basic melody into a natural minor scale, what does that sound like? Let’s give it a listen:

To a lot of people, this natural minor version of a melody sounds a little bit unusual. Specifically, to a lot of people it sounds kind of monk-ish, like it’s part of a chant from the middle ages. This is all because of what I had to do when I lowered the 7th scale degree–or B–down a half step, turning it to Bb. That note suddenly sounds kind of far away from the tonic, and it’s not pulling the ear back towards that root note in the way it does when we’re playing a major melody.

It’s also changed the chords from the previous melody: instead of being two major chords, now both C and G are minor chords.

Whether that sounds cool to you or not, to a lot of composers and musicians over the centuries it doesn’t sound as cool as it could. So lots of them decided that, when they’re playing a melody in a minor key, they should keep the 7th from the major scale so that it has that strong pull back to tonic. If we do that with our melody above, this is what it sounds like:

Ok! Now we’re cooking a little bit. Probably this melody sounds a lot more “minor” to you and less monkish. It also has the side effect of changing our harmonies–so now instead of C minor and G minor, we have C minor and G major. So we have a V major chord instead of a V minor chord.

This is why the scale that you get when you take the melodic minor scale but keep the 7th note from the major scale is called the harmonic minor scale. That scale, which is basically a major scale with a flat 3rd and 6th scale degree sounds like this:

When a lot of students of mine hear this scale for the first time, they think it sounds cool and Eastern. Which, yeah. This scale is used a lot in Jewish music, as well as other types of music from the middle east. The distinctive feature you hear as being Eastern-like is that jump from the lowered 6th to the raised 7th–an interval called an augmented second.

Again, though you might think that interval is cool-sounding, not everybody does or has. Which is why some composers and musicians have wanted to shift things traditionally when dealing with a minor scale. In order to understand why that is, let’s look at yet another melodic example. This time, the melody is going E-D-C-B-A-G-A-B-C. Another fairly typical melodic phrase that often shows up at the end of a melodic line. I’ve harmonized it with the left hand, C-G-G-C. Check it out:

Ok, if we convert that melody to harmonic minor, this is what it sounds like:

Hopefully you can hear that jump between the 7th and the 6th of the scale–in this case, a B and an Ab. It’s a little bit weird, isn’t it? I mean, could be good weird, but still weird. There might be some times when you want to smooth out that leap. One way to do that, and the way that has become pretty common practice since the 17th century, is to lower the 7th on a descending line, and raise the 6th on an ascending line. So if you’re going up in the key of C minor, you play A natural and B natural, and if you’re going down you play A flat and B flat. Let’s listen to this melody played like that so you can hear it:

At least on the way up, this version sounds quite a bit smoother. If I had enough time to fix the harmony, it would sound smoother on the way down as well. But, you know. I’m doing this for free, so this is what you get.

So the scale above is called the melodic minor scale, and it completes the trifecta of our three minor scales. We’ve got the natural minor scale, the harmonic minor scale and the melodic minor scale.

So what do you do with these three scales? How do you use them?

Well, the overall point here is that the 6th and 7th notes in a minor scale can be unstable and shift constantly. If you’re trying to write a melody in a minor key and something sounds weird, try playing around with those two notes. Maybe you’re using a harmonic minor scale where a melodic minor scale would sound better? Or maybe you’re using a natural minor scale when you might want to raise that 7th scale degree to get some more harmonic tension?

Honestly, if you’re not making music in the style of Mozart, what you do with this knowledge is up to you. But hopefully you’ve gained a tool you didn’t have before!

Your Assignment for this Lesson

For this lesson, take a song you know that is in a major key, and re-write it in a minor key. Or, alternatively, take a minor key song and re-write it in a major key. Either way, try to keep the melody as recognizable as possible in the new key. Bonus internet points offered if you can identify this song as being in either a parallel or relative minor / major key.